Rangers of the Republic of Texas

After the Revolution, "Texians" (as they were called) were more reliant on the Rangers than ever. The "Ranging men" organized by Moses Morrison and Stephen F. Austin in 1823, served as needed through the War of Independence. However, the end of the war brought an empty Texas treasury and the Texian Army was disbanded by 1838. Texas Rangers were often the only force protecting the frontiers of the new republic.

Ranger companies were called by various names: mounted volunteers, mounted gunmen, mounted riflemen, spies and minutemen. Although the names varied, these militia units were similar and performed the same function. These militiamen furnished their own equipment and subsistence. Their mission was to range the frontier, protecting settlers from Indian raids and lawlessness. Periods of service varied from a few days to several months, pay was poor and often consisted of promissory notes and next-to-worthless Republic of Texas paper money.

Surveying & Ranging

The new Republic needed surveyors to document and plat the uncharted land. The Texas Congress elected a surveyor for each county who appointed deputy surveyors.

Several Rangers and former Rangers were uniquely qualified to survey the land. Maj. George B. Erath had come to central Texas in the 1830s as a Texas Ranger and returned as a surveyor. Famous Capt. John Coffee "Jack" Hays, knew the southwest frontier well and surveyed enormous tracts during the 1840s.

Single Shot Firearm Tactics

In the early days of the Republic, Texas Rangers were usually armed with muzzle-loading single-shot rifles and pistols. When met by a larger force, Rangers dismounted and fought as a unit from a defensible position.

Their main adversaries, the Comanches, were carried bows, arrows, lances, war clubs, and extra horses. By changing horses, the Comanches could strike without warning and easily outrun the Rangers.

A favorite Comanche battle tactic was the feint: the leader sent a few warriors ahead of the main body as decoys to lure the Rangers into an ambush. They would wait until the Rangers were within range, then strike from concealment showering them with arrows.

A warrior could shoot several arrows in the time that it took a Ranger to reload a single-shot weapon. Inexperienced Rangers often discharged their weapons too soon, allowing the Comanches to ride close and fire arrows before the Rangers could reload. To combat this tactic, experienced Rangers adopted the tactic of firing in relays—one group reloaded while the others fired.

Repeating Firearm Tactics

In May of 1844, Captain John Coffee "Jack" Hays acquired Colt Paterson five-shot revolvers and revolving rifles, some sources indicate these came from from the stores of the decommissioned Republic of Texas Navy. Colt had envisioned his revolver as a military sidearm for officers and a gentleman's pocket pistol. Aside from the Republic of Texas Navy, and some officers who used them in the Seminole War, there were few buyers for the delicate .36 caliber pistol and Colt went bankrupt.

In May of 1844, Captain John Coffee "Jack" Hays acquired Colt Paterson five-shot revolvers and revolving rifles, some sources indicate these came from from the stores of the decommissioned Republic of Texas Navy. Colt had envisioned his revolver as a military sidearm for officers and a gentleman's pocket pistol. Aside from the Republic of Texas Navy, and some officers who used them in the Seminole War, there were few buyers for the delicate .36 caliber pistol and Colt went bankrupt.

In June of 1844, the Texas Rangers and the Comanche fought a pivotal battle that forever changed the history of Indian warfare in the West. After drilling his men in marksmanship, Hays fielded a company of 15 men who patrolled the area around Walker Creek northwest of San Antonio. They encountered a large raiding party. Instead of dismounting and finding a defensible location, the Rangers rode toward into the Comanches, attacking them on their flank.

Wave after wave of Comanche warriors attacked the Rangers. Each time the warriors were repulsed, suffering heavy casualties. The war chief was perplexed by the Rangers' ability to continue firing without reloading after each shot.

The five-shot revolver allowed the Rangers to fight an offensive war against the Comanche, tripling the firepower of each man by 300%. For the first time, a small detachment could successfully oppose a larger force.

The five-shot revolver allowed the Rangers to fight an offensive war against the Comanche, tripling the firepower of each man by 300%. For the first time, a small detachment could successfully oppose a larger force.

Despite the advantages of the Colt revolver, it had many drawbacks. The pistol used a small powder charge firing a round ball of limited destructive potential. The weapon could not be reloaded in battle because it had to be disassembled in three pieces to reload. The first models had no loading levers to tamp down the powder charges. And it was impossible to repair a broken Paterson in the field.

Indian Rangers

An act passed of the Texas legislature dated June 12, 1837, authorized Ranger companies to employ members of "friendly" tribes -- usually including the Choctaw, Cherokee, Shawnee, and Delaware -- as scouts and spies. Detachments of Indians served alongside Anglo and Hispanic Ranger companies. Their knowledge of the land and fighting tactics of other tribes proved highly valuable to the Texans.

An act passed of the Texas legislature dated June 12, 1837, authorized Ranger companies to employ members of "friendly" tribes -- usually including the Choctaw, Cherokee, Shawnee, and Delaware -- as scouts and spies. Detachments of Indians served alongside Anglo and Hispanic Ranger companies. Their knowledge of the land and fighting tactics of other tribes proved highly valuable to the Texans.

The Lipan Apaches and Tonkawas frequently accompanied Ranger companies into the field. For the Lipan, an alliance with the Texans was important in protecting them from their main enemy, the Comanches. Castro and Flacco, Lipan chiefs, became valued leaders and captains of their own companies.

Placido, a Tonkawa chief, often served with the Rangers as a scout from the days of the Republic through the 1850s, including at the battle of Plum Creek in 1840. However, as the tribes relocated or were removed from Texas, Indian involvement in the Rangers decreased.

Hispanic (Tejano) Rangers

During the early years of the republic, Hispanics served alongside Anglo and Indian Rangers. A number of men such as Juan Seguin and Antonio Menchaca gained reputations as skilled leaders during the Texas revolution and later used those skills in the ranger service. Some companies were composed entirely of Hispanics, but others, like those led by Lewis Sanchez and José Maria Gonzales, were a mix of Hispanics and Anglos.

Hispanos faced a major dilemma during and after the war for Texas Independence. Both Texas and Mexico demanded their allegiance. They were forced to choose between defending their homeland and defending those who shared the Mexican culture. Hispanics were sometimes forced to change loyalties for the protection of their families and livelihood. When Mexican General Adrian Woll invaded San Antonio in 1842, many families returned to Mexico with him. These strained relations between Anglos and Hispanics led to a decline in Hispanic membership in the Rangers.

Frontier Defense

Frontier defense of the new republic relied heavily on volunteer forces. Congress authorized the formation of ranger companies to supplement the small number of regular troops. Companies were typically formed by men from the same county in order to protect the surrounding area or participate in a particular battle. In essence, the settlers provided their own protection.

The men who served in the early ranging companies came from many different backgrounds. Settlers immigrated to Texas from both the United States and Europe. Frontiersmen from states such as Kentucky and Tennessee were noted for their knowledge of frontier defense. Some settlers had military experience in the U.S. Indian Wars or in European wars. Those who knew little about frontier defense soon learned the tactics necessary to survive on the Texas frontier.

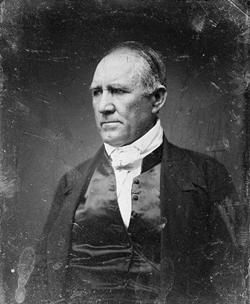

Sam Houston

Sam Houston served as the Republic of Texas' first president from October 1836 to December 1838 and later as the first Senator from the new State of Texas.. He advocated a policy of peace toward the Indians and Mexico. To prevent a Texan invasion of Mexico, he furloughed much of the restless army in May 1837.

Sam Houston served as the Republic of Texas' first president from October 1836 to December 1838 and later as the first Senator from the new State of Texas.. He advocated a policy of peace toward the Indians and Mexico. To prevent a Texan invasion of Mexico, he furloughed much of the restless army in May 1837.

Attempts at peace through treaties and trade had limited success. As settlers moved onto settled Indian lands and traditional hunting grounds, they were met with retaliation by the various tribes. With the military disbanded, frontier defense relied on militia, Ranger companies, and minutemen.

Houston was succeeded by Mirabeau B. Lamar but returned to office in December 1841. During his second term he worked to renew peaceful relationships with the Indians and avoided war with Mexico despite two Mexican invasions in 1842.

The murder of Lipan Apache Ranger Flacco in late 1842 prompted President Sam Houston to write this letter to Flacco's father. Houston's tribute to the slain Lipan is evidence of the great respect Flacco had earned among many Texans and the president's eagerness to maintain a peaceful relationship with the tribe.

Letter to the Lipans in memory of their chief, Flacco

Executive Department, Washington, Texas, March 28, 1843.

My Brother:

My heart is sad! A cloud rests upon your nation. Grief has sounded in your camp; the voice of Flacco is silent. His words are not hear in council; the chief is no more.

His life has fled to the great Spirit, his eyes are closed; his heart no longer leaps at the sight of buffalo. The voices of your camp are no longer heard to cry "Flacco has returned from the chase."

Your chiefs look down upon the earth and groan in trouble. Your warriors weep. The loud voices of grief are heard from your women and children. The song of the birds is silent, the ears of your people hear no pleasant sound, sorrow whispers in the winds, the noise of the tempest passes, it is not heard.

Your hearts are heavy. The name of Flacco brought joy to all hearts. Joy was on every face, your people were happy. Flacco is no longer seen in the fight, his voice is no longer heard in battle, the enemy no longer makes a path for his glory. His valor is no longer a guard for his people. The might of your nation is broken.

Flacco was a friend to his white brothers. They will not forget him; they will remember the red warrior. His father will not be forgotten. We will be kind to the Lipans. Grass will not grow on the path between us. Let your wise men give counsel of peace, let you young men walk in the white path. The gray headed men of your nation will teach wisdom.

[Signed] Thy brother, Sam Houston.

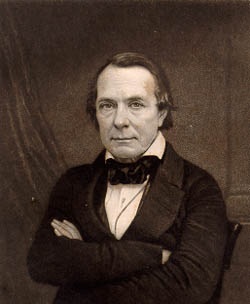

Mirabeau B. Lamar

Mirabeau B. Lamar became Texas' second president on December 10, 1838. His policies regarding frontier defense were in stark contrast to those of Houston. He believed that expulsion of the Indians from Texas was the only solution to the frontier problems. The Cherokees and several small tribes were ousted from the republic in 1839. In 1840, Lamar waged a campaign against the Comanche which helped to curb conflict for only a short time.

Mirabeau B. Lamar became Texas' second president on December 10, 1838. His policies regarding frontier defense were in stark contrast to those of Houston. He believed that expulsion of the Indians from Texas was the only solution to the frontier problems. The Cherokees and several small tribes were ousted from the republic in 1839. In 1840, Lamar waged a campaign against the Comanche which helped to curb conflict for only a short time.

Taking a more aggressive stand on frontier defense, Lamar developed plans for a line of forts along 600 miles of frontier and the enlistment of hundreds of regular troops. These goals would take time to implement, so Rangers, militia, and mounted volunteers remained the primary source of protection until the annexation of Texas into the United States in 1845.